An update by Karsten Lehmann.

More than half a year ago, Karsten Lehmann published a small piece on the RaT-Blog to contribute to the understanding of the COVID 19 pandemic. In this piece, he described the notes he saw during ‘the first Austrian Shutdown’ (in March and April 2020) in the shop-windows of the street next to his apartment – that is: in one of the urban single-digit districts (‘Bezirk’) of Vienna / Austria.

In the meantime, the COVID 19 pandemic has affected almost everybody’s life. In autumn 2020, the infection rates increased to such an extent that the Austrian government ordered a second shutdown – starting on November 17th 2020 and ending on December 6th 2020. Under these conditions, the following piece once again looks at the shutdown-notes displayed on the same Viennese street:

- On the on hand, it will argue that the shutdown-notes document a significant change in the perception of the pandemic.

- On the other hand, it seems that the shutdown is still presented primarily as a restrictive matter imposed by ‘the state’ and ‘the government’ – with all the potential consequences for future controversies.

This applies to the second as well as the third shutdown. The shop-owners have not produced any new shutdown notes for the third shutdown.

Shutdown-Notes as a Set of Data

Besides medical and virological research, the last few weeks and months have seen the emergence of a steadily increasing corpus of literature from the social sciences as well as theologies that is dealing with COVID 19. As far as the social sciences are concerned, two major points of reference seem to be the edited volumes ‘Die Corona Gesellschaft’ as well as the anthology ‘Jenseits von Corona’. Together, they present a wide panoramic view on the present-day academic discussions around COVID 19.

Most of this literature approaches the pandemic, however, from a rather general (sometimes: normative) perspective. Conversely, the following piece will occupy a decisively empirical and descriptive point of view. As indicated in the first post on this issue, I approach the shutdown-notes as a specific ‘communicative genre’ that has long been used by small businesses to announce closure – e.g. for family festivities or holidays.

From this point of view, the notes can – in first instance – be read as a legitimation of the closure of small businesses beyond legal public holidays. In this sense, they provide insights into a rather specific segment of the construction of COVID 19 that is situated between personal conversations and official statements.

Almost no Changes among the business in the street

To look at the situation in November and December 2020, I once again took pictures of all the shutdown-notes under display in the business-street next to my apartment. The pictures were taken on December 6th – that is: at the beginning of the last week of the second shutdown. In other words, the businesses were still in shutdown and it seems reasonable that the business-owners had not begun to re-open their shops, yet.

As compared to the situation at the beginning of 2020, the set-up of the shops situated in the street had not changed significantly. Only one of the businesses had to close permanently. In addition, a new surgery opened in the street that had (and still has) a display window. So, there is a total of 84 shops with display windows in the street – more or less equalling the situation during spring. The display of shutdown-notes had, however, changed significantly.

Fewer shutdown-notes in December

A comparison of the mere numbers of shutdown-notes on display in April and December presents the following picture:

- Thirteen of the businesses in the street were open during the December shutdown – primarily pharmacies and grocery stores (and the medical practice that opened over the summer).

- In December, there were, however, forty-three shops that were closed and had no shutdown-notes in their display windows (14 shops less than in April).

- This leaves a total of twenty-eight shutdown-notes on display during the second shutdown (16 shutdown-notes less than in April).

In other words, the percentage of shutdown-notes placed within the windows of the shops decreased significantly. During the first shutdown, more than half of the closed shops had shutdown-notes within the display windows. During the second shutdown only about 30% of the business-owners put respective notes on display.

This indicates that the businesses-owners were less inclined to legitimate the closure of their shops in November / December than in April. In other words, the very fact that businesses had to close down – due to a pandemic – seems to be less extraordinary during the second shutdown than in the first. It took only half a year to make such an undertaking ‘normal procedure’ – at least for an increasing segment of the shop-owners in the street under review. De facto, the business owners seemed to adjust to the situation.

Accommodation to the Situation

The analyses of the shutdown-notes suggest that it makes sense to differentiate between two sets of shops:

- On the one hand, there are the shops that can be described as franchises or subsidiaries linked to chains or a bigger institutions. In the case of the street under review, only six of the closed shops belong to this category. Under normal conditions, the mangers of these shops tend not use shutdown-notes, because they are in a position to keep the shops open all year long – using e.g. substitute staff over vacations. In November / December, almost all of these shops used prepared notes with little information.

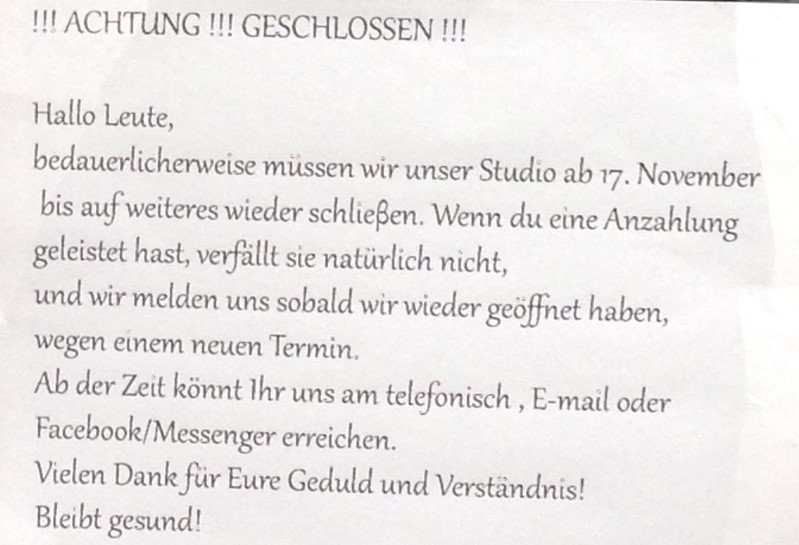

- On the other hand, there are the privately run businesses. As far as the present survey is concerned, four of them used rather simple notifications, indicating that the shops were closed (similar to the notes displayed in the windows of franchises). The owners of the remaining eighteen shops used more detailed shutdown notes, most of them personally addressing their customers (Liebe Kundinnen und Kunden) – in one case using a less formal salutation (Liebe Leute).

And there is another interesting difference between the notes displayed in the windows of those shops. None of the shutdown-notes displayed in the windows of franchises or subsidiaries provided any means of further communication (e.g. an telephone number or an email-address) with their customers. They really just communicated the fact that the respective business was closed. In contrast, twelve of the eighteen privately run businesses provided the readers of the shutdown-notes with this additional information on how to keep in touch with the respective businesses.

In some cases, the shop owners explicitly encouraged possible customers to use different means of communication to get in touch: Two shutdown-notes are particularly strong on this. On one of them it reads for example: “Um sie weiterhin mit Ware zu versorgen, biete ich ihnen folgende Kontaktmöglichkeiten … (In order to furthermore supply you with goods, I offer the following ways of contacting me)” So, the shop owner addresses the potential customers personally and underlines the significance of offering (basic) supplies to the customers.

This can be interpreted as an adaptation to the situation by bypassing the shutdown and opening new avenues of communication. Of course, I can’t trace to what an extent this avenues of communication has actually been used. Notwithstanding, such an option to keep in touch, is not part of the traditional shutdown-notes (due to family festivities and holidays). Under the conditions of the shutdown, they document an accommodation to the extraordinary situation as well as an attempt to keep the business running.

Persistent Focus on Government Restrictions

As during the pervious shutdown, the majority of the more personalized notes documents that the closure of the shops is ascribed to government-regulations. One of the respective sections reads for example: “Ab 17.11.2020 muss ich mein Geschäft wieder schließen …. / Once again I have to close my shop from 17.11.2020 onwards.” Another shop owner wrote: “Auf Anordnung der Regierung muss ich leider an Dienstag den 17.11.2020 schließen … / Due to an order by the government, I unfortunately have to close on Tuesday, 17.11.2020” And just another example: “Ich bin verpflichtet Ihnen mitzuteilen, dass auch mein Geschäft aufgrund der Maßnahmen der Bundesregierung ab 17.11.2020 bis auf weiteres geschlossen bleiben muss. / I am obliged to inform you that – until further notice – also my shop has to close down on 17.11.2020, due to the measures of the government.”

Not a single note explicitly indicates that the shutdown might help to contain the pandemic or that it might be useful to close down businesses in order to safeguard public and / or individual health. At least with regards to the shutdown-notes, the business owners certainly do not voice support for these types of measures. The notes do, however, document a certain degree of criticism – or at least discontent (Aside: The notes on the behavioural rules to be observed within the shops frequently refer to the health of employees and customers.)

This particular way to focus on the government can be read as rather limited support of the government restrictions. Of course, shutdown-notes are not the communicative genre to convey the individual convictions of the respective authors: Under normal conditions, they do not document, whether a business owner likes to attend a family gathering or not. By the same token, they presently do not document the business owner’s personal attitude towards government actions. Nevertheless, it is significant that in November / December 2020 the containment of a pandemic still does not provide the frame of reference to legitimize the closure of businesses.

Two Characteristics of the Situation

To put all of this into a nutshell, the previous analysis of the shutdown-notes highlights once again the perception that the shutdown is primarily constructed as a government restriction. The writers of these notes address the government as a source of formal restrictions. It seems to be plausible that the government will also be held accountable for the consequences of these actions. The shutdown-notes certainly do not attribute the shutdown to any type of more general good (e.g. the containment of the pandemic or the health of their customers).

At the same time the decrease in the mere number of shutdown-notes indicates that the second shutdown seems to be perceived as an incident that does not necessarily need further explanation or legitimation. Under these circumstances, the references to ways of communication that are still open to customers seem to indicate that the shop-owners accommodate with the situation – the urge to do so is more prominent among private businesses than franchises or subsidiaries.

Finally, it is interesting to see that there are no significant changes with regards to the third shutdown, already announced by the government to start directly after Christmas. This supports the interpretation that – as far as the small businesses under review are concerned, the third shutdown is primarily perceived as a perpetuation of the second one.

Prof. Dr. habil. Karsten Lehmann is Research Professor for inter-religiousness at the Kirchliche Pädagogische Hochschule Vienna-Krems (KPH), member of the RaT-Research Center, and Guest Professor for Religious Studies at the University of Greifswald / Germany. Photograph (redacted to preserve rights of shop owner) by Karsten Lehmann.

Rat-Blog Nr. 2/2021

2 thoughts on “Coping with Government Restrictions. Shutdown-Notes during the second and third Austrian Shutdown”

Comments are closed.