The controversial opening of the Olympic Games 2024 in Paris sparked an avalanche of debates on social media, as per usual. Some saw clear signs of the Apocalypse (the pale horse rider), others artistic morbidity (beheaded ‚artists‘) and eyesore discord (the dancers of Moulin Rouge) but the majority debated about the mockery of Christianity and Christians in the scene that resembles the iconic image of The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci borrowed from Italy for the Olympics. The apologetics of this obscene performance justified it by a recourse to „artistic freedom“ and the references to Dionysus.

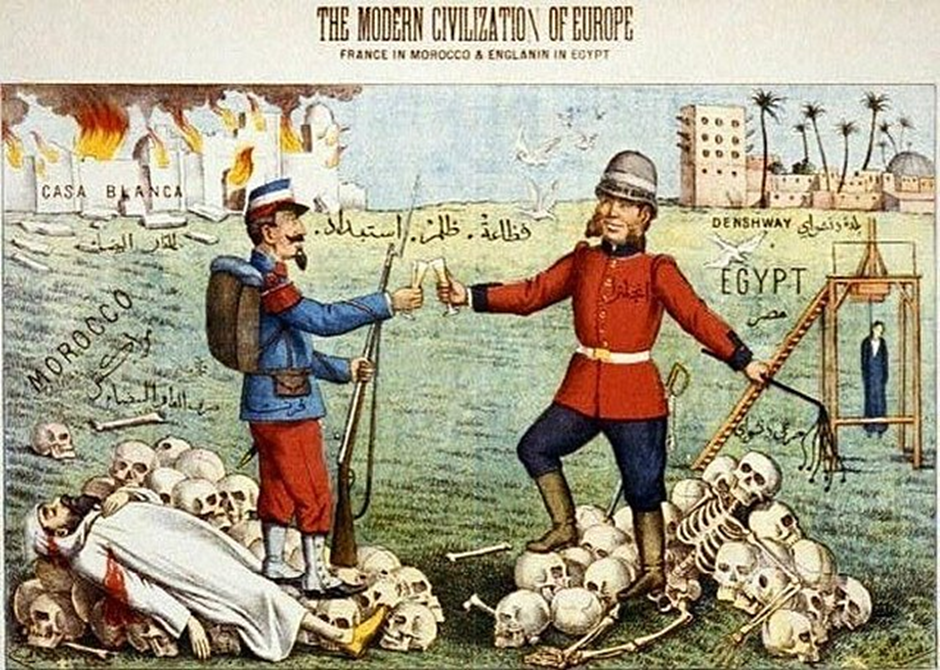

However, what was truly decadent in this performance was that France paraded its abundance, the plentifulness from which it has been built – its long history of colonialism and exploitation. Apparently, France did not join the movement of the so- called cancel culture that for some peculiar reason usually goes hand-in-hand with this kind of performance. Instead, it threw to the hungry, war-torn world the most obscene colonial, neo-post-capitalist, tycoon-like corporate abundance.

It was a slap. The athletes turned the other cheek and moved to the hotels to seek egg-based food and real beds. The celebration, the organizers claim, was not a mockery of Christianity, but incorporation of cultural – artistic (pseudo-religious one might add) heritage. This so-called heritage, performed in an exhausting neo-pagan ceremony, that the rest of us ’narrow-minded‘ somehow misunderstood, is precisely the heritage of colonial France (and not only France), eating from the platter of shame provided by the flesh of its colonies.

What is the political message of this cultural introduction to the Olympic Games? For let us not forget that “culture is the biggest ideological arena” (Slavoj Žižek).[1]

The political message is not tolerance and integration. On the contrary, it is intolerance – for a self-indulgent and self-centred society cannot be tolerant. It is not integration – for it requires equal distribution of wellness and justice, recognizing plurality that does not create polarized masses and that supports the right to life of every human being. France chose the platter of abundance, while previously cleaning the Parisian streets from ‚garbage‘ and immigrants, the two been equalized in the swift process of putting perfume[2] on a dirty corpse.

France, only kilometers away from Ukraine and the Balkans who are fighting a historical ecological battle of the era offered to some ‚chosen groups‘ of people to feast until they die in the meaningless plentitude of the ‚earthly fruits‘. These earthly fruits will not be offered to the children of Gaza either, as one would expect. Instead, they are offered to chosen masses the decadence once reserved only for the elite (Žižek).[3] In doing so, France galloped into nothingness, shamefully displaying its lack of consciousness and empathy. And this is the political message: we do not care. France drowned its own values in the river Seine.

Shamefully feasting from the plate of abundance, it revealed its true face and idea: that it has no idea and no face. Perhaps it was society’s last supper indeed, but after which there will be no resurrection, for France just literally cancelled itself.

The rest of the world, wrestling with different types of challenges can rest in peace, for their struggles are bearing the cross or even being nailed to the cross. And we know what happens afterwards.

Milja Radovic

[1] Slavoj Žižek in Milja Radovic: Transnational Cinema and Ideology: Representing Religion, Identity and Cultural Myths, New York: Routledge, 2014/2017, pp. 89-90.

[2] “While the use of perfumes was for a long time considered suspicious because it could be used to cover up a lack of hygiene (Corbin, Foul), it is considered here as a sign of bad manners, the result, in the moral register of the time, of dirtiness.” Érika Wicky: “The Olfactory Education of Young Women in Nineteenth-Century France” in Women’s Studies, New York: Routledge, Vol. 51, Issue 7, 2022, 727-743

[3] Slavoj Žižek in Milja Radovic: Ibid.

Photocredits: (C) Wikimedia Commons

RaT-Blog Nr. 15/2024