Important notice: This article was authored on 2 March 2025, prior to the most recent developments; the author attempts to reflect on specific notions and issues rather than provide definitive answers.[1]

In a world with deepening divisions, corruption, warfare, vengeance, and chaos, the twin forces of apathy and isolation thrive amidst widespread confusion. The challenge facing theologians, philosophers, political theorists, and other thinkers is to explore avenues for transforming a society that appears to be nearing its demise – marked by self-denial and self-destructive tendencies (where the state prioritizes its own interests over those of its citizens) – while simultaneously upholding the rich tapestry of pluralism. The question of power dynamics, the misuse of power on one hand, and the sovereignty of individuals and communities on the other, remains both perilous and essential.

Re-examining Christian thought and its profound implications for the restoration of society is essential: in societies that cease to serve their citizens the antidote for apathy and isolation is found in community, an active state of being. Liturgical communion and community are inextricably linked as “being is communion.”[2] The concept of being as communion embodies the freedom to love and to sacrifice for the ‘other’ – it represents “faith in action.” [3] Such action manifests as praxis, a continual act of “becoming a person”, from image to the likeness of Christ. The life of asceticism, which extends beyond monasticism, is an ongoing act of praxis – always purposeful, though not politically motivated. Community, being at the heart of both ascetic and Christian praxis, defies political categorization – it is anti-political, and in that it fosters rapture rather than rupture. The yearning for community and societal transformation is deeply theological (being as communion[4] and change as transformation – metamorphosis). Yet the challenge lies in how we interpret these principles within concrete political contexts and during times of institutional crisis.

Let us turn our attention to the recent political crisis in the Balkans, aspiring to deepen our understanding of the complexities involved:

The Novi Sad railway station canopy collapse on 1 November 2024 that killed fifteen people resulted with the not-the-first – but the-biggest student uprising in the twenty-first century. The unprecedented tragedy of Novi Sad is not the first but the last in a series of different tragedies and incidents that shook the state of Serbia (Rio Tinto[5]) in recent decades. The students have awakened: for the past three months, the blockades at universities in Serbia have not only persisted but have intensified, garnering recognition and support from across the former Yugoslavia. Meanwhile, Europe and the rest of the world seemingly look ignorant, or indecisive, within their own (media) universe preoccupied with their own political misdemeanours and follies, pretending not to have interest in the area.

Students and those who support them created a strong sense of community that the area did not see for a very long time, since the last protests. Students and citizens in turn have been heavily criticised: from being accused of not being very clear and using the ‘plenum model’ to accusations that they were ‘foreign mercenaries’ (or in best case, the opposition’s “useful idiots”) who are leading some kind of the old-new coloured revolution. The last does not hold-up: the demands of the students, largely supported by citizens of all backgrounds, does not seem to be aimed at overthrowing the Government and the President of the State, therefore coloured revolution as we know it is excluded. The demands appear to be straightforward: they call for the release of all documents pertaining to the reconstruction of the Novi Sad railway station, a call for institutions to operate transparently and effectively, an end to corruption, and the identification of those responsible for assaulting both students and their professors. [6]

The perseverance of the students and the backing of the community motivated students from “the region” to emerge, marking what may be the first instance that so powerfully brought together those who were once divided. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize the paradox of the unification, which also led to certain divisions. Some citizens initially did not support the students for various reasons, while others chose to remain neutral, refraining from expressing a clear stance for or against the blockades, perhaps because of political apathy as the process of lustration never took place. There have been citizens who were not clear on who exactly supports the students, whether this is yet another ‘project for the Balkans’ or not, and what is the exact solution for the revival of constitutional democracy, the elimination of corruption and the restoration of the legal system. The suspicion of some citizens perhaps comes from 30-year-long experience with those who have held on to power rotating their roles while claiming that there are ‘two Serbias’ (one progressive and one nationalistic-regressive). We should not neglect also the popular opinion that the disintegration of Yugoslavia and everything else that followed was an experiment that other European countries experienced later (or are yet to experience) and that the Balkans is the playground of superpowers who have different economic interests wrapped in different ideologies as well as that some other citizens wondered why no similar action took place when it comes to the question of Kosovo. In that sense, whatever the course of events might be, those citizens who remained undecided must be addressed not only by words but a satisfactory political message and a promise that will be fulfilled visibly, such as for example in juridically protecting the land and natural richness, resources and habitat, preventing anyone in power from selling it to foreign (or domestic) companies. At the time of writing this article, there appears to be an increasing number of supportive citizens rather than a decline, even though confusion persists among many. Yet at the same time, the blockades were supported across the diaspora and all the continents. But what is the pressing question at hand? It is not so much whether the students provide a definitive political solution, but rather how their actions signify an effort to reform the system and bring together various factions of citizens and movements, such as the ecological uprising against Rio Tinto. This manifested, symbolically in the culmination of the events that took place on the Statehood Day also known as Sretenje (The Meeting)[7] on 15 February 2025, when exhausted students walked across the country to Kragujevac chanting Vostani Serbije (‘Arise Serbia’)[8] and sending a clear message: respect the constitution, end the corruption, create a reliable and strong institutional system. In the series of many dramatic and serious events over the past months, one might ask: why single out this event? The answer is simple: first, this date is directly connected to the First Serbian Uprising in 1804 under the Vožd Karađorđe Petrović, and secondly because on this date in the year 1835 in the town of Kragujevac the first modern Constitution of the Principality of Serbia (Sretenjski Ustav) was adopted, establishing the separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial, and as such was one of the best constitutions of its time, being based on the principles that are regarded as a cornerstone of democracy and constitutional governance today. Led by the idea that all the institutions must respect the constitution, that is, turn into practice ‘a dead letter on paper’, the students continue their march.

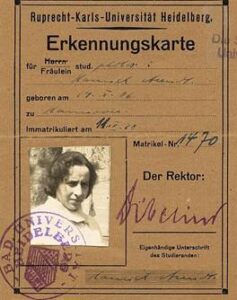

It is useful to remember here Hannah Arendt’s philosophical and political thought on promise – the new beginning and forgiveness[9]: the faculties of forgiveness and promise can be enacted only in the presence of ‘other’, that is, it is a communal act. It is on these faculties that our identity and our capacity to act are based. Forgiveness in Christianity is bound to love for the uniqueness of human being – person, and this holds human relations together. However, Arendt goes further arguing that forgiveness and compassion must become the guiding principles in the public sphere. Love is for Arendt “anti-political”, and she considers respect as something that is in the larger domain of human affairs, and when the respect is lost, it is a clear symptom of depersonalisation in the public sphere. Freedom is bound to both love and forgiveness, and freedom is a promise of a new beginning: “The miracle of freedom is inherent in this ability to make a beginning, which itself is inherent in the fact that every human being, simply by being born into a world that was there before him and will be there after him, is himself a new beginning.”[10] Enacted compassion and the return of empathy and respect into the public sphere, the capability to demand rights for others (e.g. victims) but not to enact vengeance, to have that leap of faith to break with the vulgarity of depersonalisation and begin something new and after all – to be the new beginning – are not these the lessons that should be drawn from this uprising that defied the lethargy of the ‘isolated masses’?

The Serbian Orthodox Church, prior to the blockades, has been emphasizing the importance of forgiveness, love (versus tolerance) and community. However, the problem arose with the protests, and the blockades, when it was expected from the Church to clearly take a side. To this again the Church responded that Communion (Liturgy) is a communal act and that its clergy as well as the faithful are free to act according to their conscience – but that it is not the place of the Church to lead a political event. This argument has been further exemplified through the example of Patriarch Pavle who in the 1990s broke the cordon of the police but by the leading the procession, not the political protest, possibly preventing a bloodshed.

A similar example can be found in earlier history when – in 1937 – the procession turned into the Bloody Procession (by which name it would remain known in history books). Of course, at that time this was a religious question, the Concordat Crisis in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, but since the citizens were involved and beaten by the police that equally beat the clergy, it is difficult to draw a line in the sand and differentiate in this case the nature of political and religious protest. This is also perhaps due to the fact that some citizens belong to specific religious groups.

Perhaps the good example of a protest to understand the nature of the religious and political and their sometimes intertwined relationship lies with one of the most massive and longest protests in recent history: the citizens’ uprising under the slogan We Will Not Give Up Our Churches (Sacred Spaces) was against the proposed Venice Commission law on freedom of religion[11] that aimed to confiscate the Churches, Monasteries and their lands built on the territory of Montenegro before 1 December 1918 when the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was founded. The paradox of the law prompted the citizens who with the Church clergy successfully stood against state confiscation of some of the oldest religious sites in Europe.[12] This was a matter of deep religious significance that fuelled the citizens’ protests, which manifested through grand processions, and ultimately sparked a political transformation, culminating in the eventual dismissal of the law in question.

Montenegro, January 2020

Returning to the topic of the ongoing blockades it is certain that this area of the Balkans is no stranger to political upheavals and protests which is not necessarily a disadvantage. In this case the plurality of society should be primary and if the author of this text is to add one more demand it would be a blockade against ignorance, relativism and political vulgarity from whichever direction it may come. ‘The defence of the Sretenjski Ustav’– Constitution – in Kragujevac, resulted with the proclamation of the ‘Student Edict.’ On 1 March 2025 in the city of Niš – the birthplace of the Emperor Constantine – the students read the document called the Student Edict (allusion to Constantine’s Milan Edict) where they declared the values and their pledge for the future in an exposé of eight major points: I) About Freedom: Serbia is a country of free people, freedom is not a mercy but a basic right inseparable from human dignity, it is the foundation of the society, law, freedom of speech and freedom of thinking; II) About the State: the state is the common good of all citizens and the institutions must serve the people and be a foundation of trust, not an instrument of the power of individuals, political office means service to citizens and not a privileged status; III) About Justice: justice is the basis of a stable society, an independent judiciary, free media and institutions must act according to the law and not political pressure, equality of rights must be a reality for every citizen; IV) About the Youth: young people are not only the heirs but the defenders of the Constitution, the youth is looking for a system based on effort and knowledge; V) About Dignity: we stand for a society in which the dignity of every person is respected and no person should be put in a position of humiliation, a country where experts are not underestimated and where knowledge is valued more than obedience; VI) About Knowledge: science, research, education and culture should be the priorities of the development of Serbia, universities must be independent and not a trading ground for degree buying and political influence; VII) About Solidarity: the roads of our cities from Niš to Novi Sad, from Belgrade to Kragujevac bear witness to the strength of national unity, Serbia is not a collection of divided interests but a community of citizens; VIII) About the Future: Let this Edict be our obligation and a pledge that we will build the state that belongs to everyone in which the government will serve the people (and not vice versa).[13] It is interesting that values (but also strong national state and rights) seem to be central for the political transformation. ‘The Edict’ provided the political tone, which is an alternative to institutionalised chaos. Its long-term aim seems to be to bring something novel, constructive and transformative into the political sphere and the institutions, through (political) action. The question that remains is who the political actors will be, how these values will be guaranteed, and to what extent and in what ways this will be beneficial for the citizens, the state, the rest of “the region” and for Europe. Perhaps the newfound sense of unity transformed into political action will prevent the exploitation of the land and ecological disasters, but this is still uncertain, as different actors have interests in exploiting the land that being outside the EU is not protected by the laws of this suprastate.

Perhaps this is a chance for re-thinking the political processes in the boiling Europe, and a chance for re-discovering and redefining the new meanings and models of democratic society which could potentially prevent catastrophes, and as some academics pointed out become an example before the next sky-fall.[14] In the further re-thinking of protest (or blockade in this case) as the means and a possibility for transformation and unification (versus the imposition of aggressive ideology and unified isolated masses or society of violence and exclusion that prioritizes the exclusivity of one group over another), it is central to remember that only if communal act(ion) holds human relationships together (both in theological thought and political theory), the action can truly be fruitful and valuable. Another question to consider in theological (and political) thought is the authenticity of genuine act (versus fabricated activism) that aims to bring novelty in human affairs which as such cannot be separated from the theological understanding of community. Otherwise, generally speaking, any form of action is doomed to fail because transformation depends on centralising values encompassed by compassion and freedom. Perhaps this year will be abundant in raspberries – they say they are the most fruitful product of the region. They are exported due to their abundance, much like students, or their ideas.

Emperor Constantine

The Defenders of the People: Skull Tower Niš

[1] Reference to the film The Year of Living Dangerously (Peter Weir, 1982).

[2] Zizioulas, John: Being as Communion.

[3] http://holywisdomorthodox.com/worship/articles/undertsanding.html

[4] Zizioulas, John: Being as Communion.

[5] https://rat-blog.univie.ac.at/?p=4171

[6] The demand for the increase in the budget for higher education I leave to the judgement of the readers, as I find it self-explanatory.

[7] Named after the Christian Feast of the Meeting of our Lord (Candlemas, Feast of the Presentation)

[8] A poem written by Dositej Obradović (1739–1811) and published in Vienna in 1804, it is dedicated to Serbia and her brave warriors, and to their leader Karadjordje Petrovic.

[9] The Human Condition.

[10] The Promise of Politics, 112, 113.

[11] Last Accessed: 23.02.2025: https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-REF(2019)014-e

[12] Montenegro is a complex matter not only as state borders were changing but also as the jurisdiction of the bishops was also spreading across the ever-changing borders. It is important to remember that Montenegro – in different borders than today – had a theocracy for over three centuries and the Prince Bishop of Montenegro was also the head of state.

[13] This is the text of the Student Edict. Miljana Isailovic, Nova.rs, 1 March 2025.

[14] Reference to the film Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012).

Image sources:

Image 1: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Raspberries.jpg

Image 2: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Student_hat_2.svg

Image 3: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hannah_Arendt_Heidelberg_University.jpg

Image 4: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Protest_in_Podgorica,_Jan_2020.jpg

Image 6: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skull_Tower_%E2%80%94_%C4%86ele-kula_12.jpg

RaT-Blog Nr. 6/2025