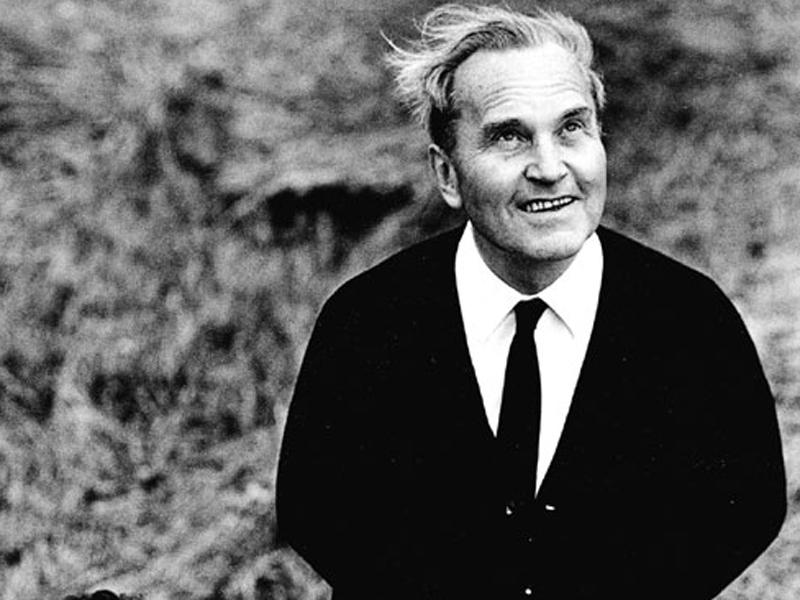

Martin Kočí draws a precise interdisciplinary portrait of one of the most original thinkers of the past century: The Czech phenomenological philosopher Jan Patočka (1907-1977) is famous for committing a number of intellectual heresies throughout his professional career. Moreover, the title of his widely read master piece Heretical Essays in the philosophy of history suggests that the transgression of boarders is somewhat a custom.

Although Patočka’s text contains more than just one heresy, for example, with regard to Marxism (the official philosophical doctrine of the time and place where Patočka lived and worked); with regard to Husserl (especially to his effort to lay down a rigorous foundation for scientific knowledge); with regard to Heidegger (by taking his ‘ontological difference’ back to the context of Christianity); perhaps the most fascinating and enigmatic one is Patočka’s reinterpretation of the role of Christianity in a post-Christian, rapidly transforming world.

In the wake of Husserlian heritage, Patočka always stresses that philosophy and theology are two separate disciplines. ‘The philosopher must eternally walk on earth,’ writes the Czech author in one of his early texts from the 1920s. He never abandoned this creed and remained faithful in this respect. Yet this does not prevent Patočka from stating extremely interesting things about Christianity. In one of the culminating points of the Heretical Essays, he confesses that ‘Christianity has been the highest and unsurpassed rise of human being in the struggle with the possibility of fall, but also something which has not yet been thought through to its end.’

Minds trained in theology must be pleased to read such words in an author who can hardly be described as a philosopher of religion. However, how shall one understand a paradoxical argument that Christianity ‘has not yet been thought through to its end?’ It seems that Christianity is presented as the drive of human existence which has not yet been thought adequately. Patočka challenges us to think of Christianity in a more existential terms, as a way of life and mode of being, rather than in terms of confessional allegiance and the adherence to certain doctrines. One of the fundamental tenets of life and being, in Patočka’s opinion, is motion. In other words, the idea concerning something un-thought in Christianity transgresses a traditional metaphysical perspective of unmoving stillness of eternity which Christianity is about to proclaim. Where does this balancing on the edge of heresy lead us?

By its very definition, the concept of the un-thought refers to something that has not yet been thought. The un-thought is something forgotten, omitted, something which has not been taken into account because of ignorance. Or, the un-thought is perhaps something that cannot be thought because of a particular historical situation which constrains the possibilities of its appearance. This would mean that our situation lacks the possibility for something to be thought. In one way or another, we have either lost the openness or we are waiting for the openness to come.

However, the un-thought can also be considered as something partially thought; a thought that is not yet finalized, and perhaps never can be. This notion of the un-thought would fit the Christian conception of dogma. A typical way of seeing dogmatic statements is their identification with closing declarations, rigid definitions, irreversible propositions and the expression of metaphysical truth. However, this perspective fails to think of dogma as a new opening and the call for further thinking and questioning; as a pointer or a sign that something has been thought.

Nonetheless these points of view seem plausible, what if Patočka had in mind somenthing utterly different, that is, something which transforms our understanding to Christianity. The previous cases consider the un-thought to be a provisional state of affairs which awaits eventual completion. The un-thought is a lack to be remedied, a question to be answered, and a limited perspective in need of broadening. The un-thought looks for a thought. In contrast to this, I dare to raise a few (heretical) questions: what if the core of Christianity, according to Patočka, is the very movement of thinking; the moment of thinking again, thinking after, a constant movement of pointing beyond itself? What if Christianity’s vocation is to manifest itself as an after-thought? What if the highest and unsurpassed rise of human being advanced by Christianity consists in an ever recurring task of thinking and living in particular historical conditions?

Obviously, we part here our ways with Patočka’s philosophy and stretch the argument into theology more than he would ever allow us to do so. Even though one would agree with Patočka that ‘the philosopher never helps the the theologian’, it does not necessarily mean that the engagement with philosophical reasoning leaves theology unresponsive. On the contrary, philosophical reflection, and Patočka’s case is an example par excellence, exposes the problematicity of everything, including Christian suppositions. Thus, from a theological perspective, such an engagement with provocative and even heretical thinking might be a truly transformative experience. And the notion of transformation is in a close proximity to conversion (a term with an explicit religious meaning which we also find in Patočka). Now the question is: what kind of conversion are we facing?

Althought the idea of un-thought might, at first sight, suggest somewhat mystical, I argue that the lesson to be drawn from Patočka is exactly the opposite one. Analogously to the conception of life as movement, the task of thinking, we are called to adopt, must be understood as fiens rather than factum. Thinking the un-thought is an event happening. In other words, we are not done with Christianity, its dogmas, its good news and the way of life it proclaims. We have not reach the ultimate, absolute end that must repeated, but the Christian mode of being searches for its goal in every moment of history.

Thus, to correct our previous point concerning the conversion of Christianity, the point is not to formulate a contextually relevant version of Christian religion in a rapidly transforming world of post-modernity, post-Christianity, post-truth or whatever signifier we use for its description. The challenge of Patočka’s heretical reading of Christianity is to become aware of the possibility of coming to conversion while puting the tradition and heritage under the scrutiny of problematicity.

How shall one do it? Patočka proposes an aswer in one of his letters to a certain Protestant theologian of his time, and I cannot find any better way to express it: ‘the point is not only to live faith, but also to think it.’ In this sense, even the philosopher who must eternally walk on earth is capable of touching the stars above.

Rat-Blog Nr. 2/2018