The talk of utopias is part of the Christian tradition. It is tantamount to a dream for the future and at the same time a critique of the present reality. Mirijam Salfinger sees ecofeminism from Latin America as a meaningful utopia in the face of the crises of our time.

It is no longer possible to imagine our vocabulary without the term crisis. The front pages of our media landscape regularly report on financial crises, migration crises, the Corona crisis, the Russian respectively Ukrainian crises and the associated energy crisis, as well as the environmental crisis, which is increasingly referred to as a climate catastrophe.

Looking at the last few years, it seems that we as a society, as Europeans, as part of the world’s population, are not only facing multidimensional and global challenges, but are going from one crisis to the next. In response to this, voices have been and continue to be raised calling for change and vehemently demanding it. This raises the question of alternatives and a new path that gives us hope for the future.

Perspective of the marginalized

The Brazilian theologian, philosopher and ecofeminist Ivone Gebara also speaks of the need for a new utopia.[1] The starting point of her reflections is the perspective of marginalised people – especially those of marginalised women she works with in Recife, Brazil. They suffer daily from the effects of a society permeated by patriarchal structures and capitalism. The care and nurturing of family members is mostly the responsibility of women, which is why they are often the most affected by the impacts of ecosystem degradation.[2]

The goal of an ecofeminist utopia is to build a world where poor and marginalised people have a place to live in peace and dignity based on justice, equality and solidarity. This is a political and, above all, a creative challenge that we must take up. If we do not choose the life of the planet and respect for all living beings, this is tantamount to choosing our own death. In order to respect the right to life of all species as well as the common good, new ethical reference points for human coexistence in community are to be created. Religious convictions must not stand in the way of this common project – Gebara therefore pleads for interdenominational cooperation. In view of this challenge, one must remain open to other approaches, positions and utopias. It is much more important than insisting on one’s own position to become aware of the common concern: The struggle for a new international order in which people respect not only each other but also the environment. This requires a critical analysis of what is going on in the world right now in order to find out what a common utopia could be for all of us.[3]

And a new utopia, a form of hope, is what people need – what we need – in view of the increasing number of excluded groups; in view of the increasing destruction of various plant and animal species; in view of the fact that wealth continues to be increasingly in the hands of a small elite. Gebara emphasises that humanity – and with it the environment – is (self-)destroying itself as a coherent body.[4]

Utopia Ecofeminism?

Ecofeminism addresses precisely this interrelated destruction and thereby combines feminist and ecological thinking. The basic thesis is that the root of the oppression and exploitation of women as well as the exploitation and destruction of nature lies in patriarchal thinking. This is not a theological current per se, but a worldwide movement that can be found in both the secular and religious spheres. Especially ecofeminism in the global South also addresses the exploitation through colonialism, so it is also a postcolonial movement.[5]

The aim of an ecofeminist utopia is to put an end to structures of oppression and violence, both in relation to gender relations and in the relationship of people to nature. In doing so, the patriarchal worldview is criticised and a holistic and relational view of being human and of the world as a whole is developed as a counter-design. Gebara emphasises the need to unite the feminist and ecological struggle, because the option for the poor also includes the option for the survival of the ecosystem and nature as a whole.[6] According to her, ecofeminist theology in Latin America is a concern of minorities – especially female minorities. „It is a way of thinking that echoes some of the cries of the growing mass of the marginalised in search of survival and dignity.“[7]

Colonialism, sexism and the exploitation of nature

A central point of ecofeminism in general is the critique of dualisms whose origins are located primarily in the European worldview. At the centre of the critique is above all the still predominant juxtaposition of man and nature, of culture and nature, of man and woman, and of intellect and emotion. In each case, the first – i.e. man, culture, man and intellect – correlate with the second – nature, woman and feeling – which is accompanied by a subordination and superiority. The respective other – i.e. nature, supposed non-culture and women – are seen as needy, subordinate and inferior. This legitimises the right to exploit and dominate them. Since colonialism, sexism and the exploitation of nature not only have a common root from the perspective of ecofeminism, but also numerous overlaps, they must also be overcome together.[8]

Relating to each other

These dualisms are countered by the principle of interrelationality. According to this, the multiple interrelationships between all things, nature, living beings and people, as well as between people of different genders with different ethnic origins from different cultural contexts, are accompanied by diverse forms of mutual dependence. This interrelatedness is seen as an opportunity for common and individual growth and thus as wealth.

According to Gebara, this interconnectedness does not only exist among humans or between all living beings, but also includes nature as a whole and the entire cosmos. She contrasts Eurocentric rationality with the idea of an ecological community of all with all and everything. In doing so, she criticises both androcentrism and anthropocentrism and pleads for an inclusive anthropological frame of reference that is not idealistic but realistic, not dualistic but holistic, not one-dimensional but multidimensional. Gebara vehemently emphasises the interrelationality of these structures of oppression and stresses that therefore a profound and comprehensive change is needed. She is convinced that the individual struggle of groups and individuals, while helping individuals, cannot change the structures that create unfair life situations. However, she does not question the need for individual and local action, but emphasises, with reference to global interconnectedness, that above all international action is necessary in the struggle for global social peace.[9]

The global connections that Gebara, and with her many other ecofeminists, bring up cannot be denied.[10] The global connections that Gebara, and with her many other ecofeminists, bring up cannot be denied in relation to the climate catastrophe, and in recent years we have become increasingly aware of them and have been reminded of them through the crises mentioned at the beginning of this article . From today’s perspective, Europe’s responsibility in the context of global interrelations can no longer be negated. This is also shown by the examination of Europe’s colonial history and theories of dependency such as the “dependency theory” or postcolonial analyses.[11] The demand for a common ethical horizon seems appropriate not only in view of the crises already mentioned, but also in view of the pluralisation of society, which continues to pose a multitude of challenges to politics and to people themselves. In order to (once again) be able to look to the future together with hope, ideological, territorial and not least confessional boundaries must be overcome. Gebara’s ecofeminist approach revives precisely this hope for a common future, which is why the discussion of it seems more worthwhile than ever, especially from a European perspective, in view of current multidimensional challenges. In my opinion, the interweaving of ecology and feminism, of the critique of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchalism is not only in tune with the times – and thus, theologically speaking, responds to the signs of the times – but also holds great potential, especially for (European) theology. Looking beyond one’s own borders – as in this case to Latin America – also shows, among other things, the necessity of deconstructing Eurocentric perspectives within theology and thus reflecting on one’s own frames of reference in each case. By taking into account the interdependence of all, by working for an end to exploitation and liberation from structures of oppression (which do not only involve human beings), ecofeminism represents a desirable response to the challenges of our time.

[1] She was born in Sao Paulo in 1944 and joined the Augustinian Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady in 1967. A student of Jose Comblin, a Belgian-Brazilian liberation theologian, she was a lecturer in philosophy and fundamental theology at the Institute Teológico Recife (ITER) for several years. Today she lives near Recife, Basil and works with marginalised women, among others.

[2] Cf. Gebara, Ivone, Ecofeminism. A Latin American perspective, Crosscurrents (2003/1), 93–103, here: 95.

[3] Cf. Ibid. 99f.

[4] Cf. Ibid. 101.

[5] Cf. Gebara, Ivone, Ökofeminismus, in: Gössmann, Elisabeth, Wörterbuch der feministischen Theologie, Gütersloh2 2002, 422-423, hier: 422.

[6] Cf. Gebara, Ivone, „I feel myself like someone who loves to drink from different waters”. Interview with Ivone Gebara, Brazil, in: Missionswissenschaftliches Institut Missio e.V. (Ed.), Jahrbuch für kontextuelle Theologie (7), Frankfurt a. M. 1999, 30.

[7] Gebara, Ivone, Intuiciones Ecofeministas. Ensayo para repensar el conocimiento y la religion, Madrid 2000, 32.

[8] Cf. Gebara, Ivone, Ökofeminismus, in: Gössmann, Elisabeth, Wörterbuch der feministischen Theologie, Gütersloh2 2002, 422-423, hier: 422.

[9] Cf. Gebara, Ivone, Ecofeminism. A Latin American perspective, Crosscurrents (2003/1), 93–103, here: 96-98.

[10] See: Eaton, Heather, Introducing Ecofeminist Theologies (IFT 12), London [a.o.] 2005.

[11] See: Silber, Stefan, Postkoloniale Theologien. Eine Einführung, Tübingen 2021.

This article was published in German before on the website y-nachten.de: https://y-nachten.de/2023/05/eine-oekofeministische-utopie-die-hoffnung-auf-eine-gemeinsame-zukunft/

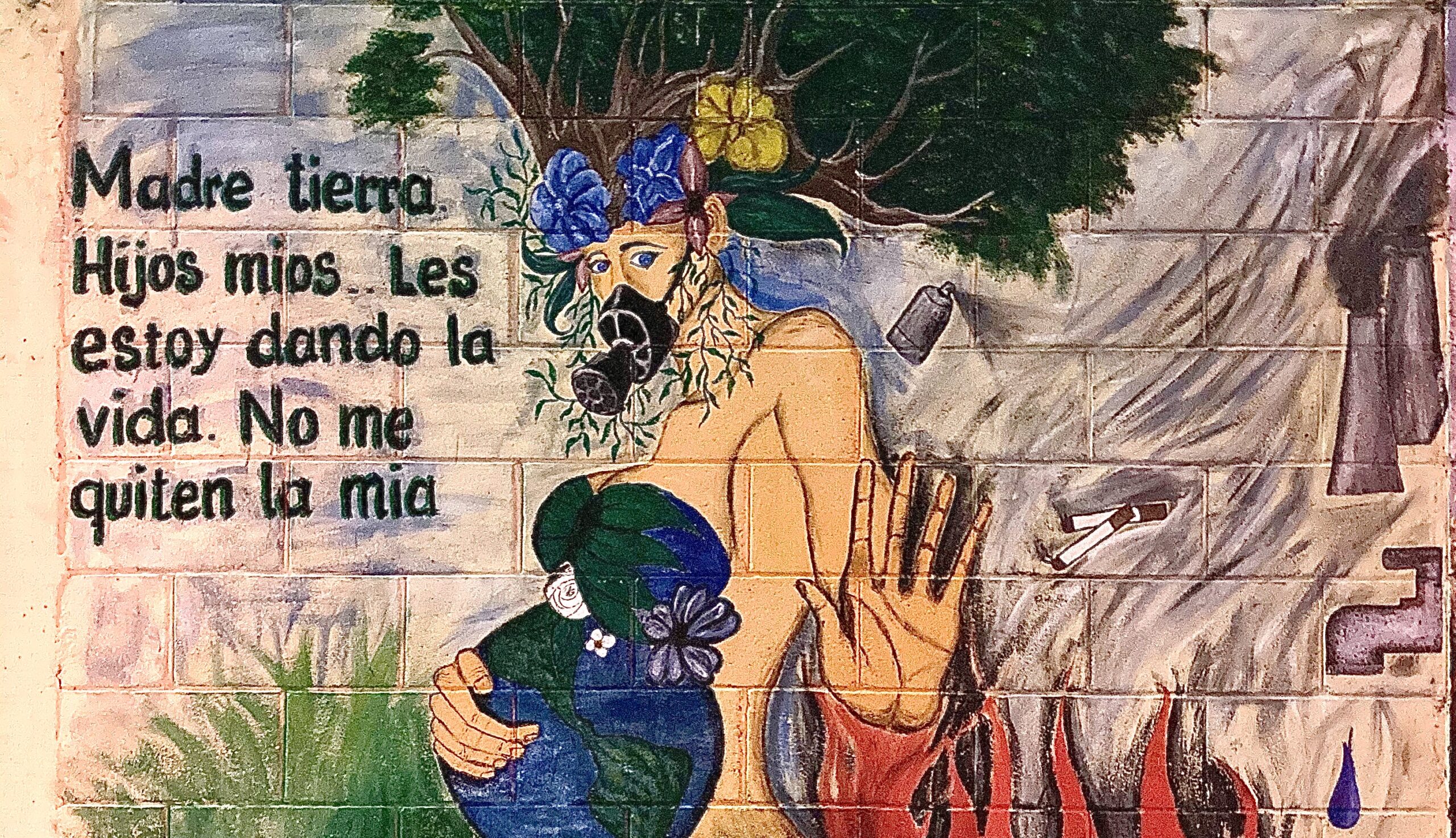

Beitragsbild: aktivistische Straßenkunst in El Salvador, fotografiert von Mirijam Salfinger

RaT-Blog Nr. 09/2023